What caused acute liver failure in some customers, including children, is still unclear.

At least 25 people in two states were likely poisoned by toxic batches of the “Re2al Alkalized Water,” including five children who suffered acute liver failure and one person who died.

That’s according to a report published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Thursday, which lays out the findings of a multistate investigation into the toxic water. Health investigators suspect additional poisonings went undetected. They noted in their report that hospital records indicated an unusual spike in unexplained “toxic liver diseases” around the time of the poisonings.

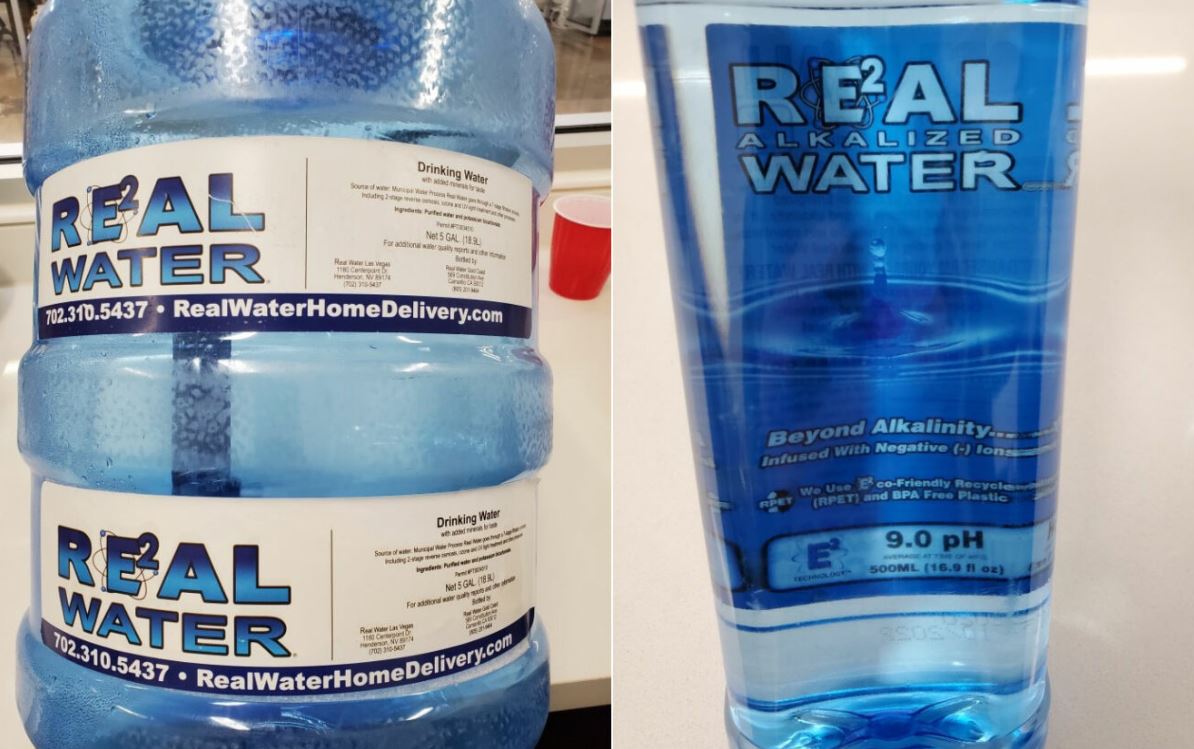

The toxic water made headlines earlier this year when health investigators initially linked alkalized water sold by Nevada-based water company Real Water to severe illnesses in five children in Clark County, Nevada. But the new report from the CDC offers the most complete look at the identified cases and illnesses.

Poisoned water

The saga began in November and December of 2020, when the five children—ranging in age from seven months to five years—became severely ill with acute liver failure after drinking the water. They were hospitalized and later transferred to a children’s hospital for a potential liver transplant—though they all subsequently recovered without a transplant. Local health officials investigating the unusual cluster found that family members had also been sickened. The only common link between the cases was the alkalized water, which Real Water claimed was a healthier alternative to tap water.

In mid-March, the Food and Drug Administration contacted Real Water about the cases and urged the company to recall their water, which was sold in multiple states, including Nevada, California, Utah, and Arizona. Real Water agreed to issue the recall. However, by the end of the month, the FDA reported that retailers were still selling the potentially dangerous water, and the regulator tried to warn consumers directly. By then, Nevada health officials had linked the water to six additional cases, including three more children, bringing the total to 11.

Now, according to the new report, the tally has increased to 25: 18 probable cases and four suspected cases in Nevada, as well as three probable cases in California.

The 21 probable cases all had an inexplicable onset of liver inflammation, with no viral infection or other underlying disease to explain the illness. They also all drank Real Water’s 5-gallon Re2al Water product. Most of the cases occurred in November 2020 and, apart from the children, were in people older than 30. Their common symptoms included fatigue, vomiting, decreased appetite, dizziness or vertigo, and unintentional weight loss. They all suffered from abnormal liver function, and multiple people were considered for liver transplants.

All 21 probable cases ended up hospitalized, and 18 required intensive care. One woman in her 60s with underlying medical conditions died of complications from her liver inflammation.

In May, the Department of Justice filed a lawsuit against Real Water Inc. on behalf of the FDA, alleging the company’s officers—Brent A. Jones and his son, Blain K. Jones—were selling adulterated products that were made amid a slew of manufacturing violations. On June 1, the Joneses agreed to settle the case, and the DOJ bound them with a permanent injunction from ever preparing, processing, or selling water again.

Toxic manufacturing

To date, it’s still unclear what exactly was in the toxic water, though. According to the DOJ’s complaint, the Joneses processed municipal tap water “by carbon filtration, reverse osmosis filtration, ultraviolet light filtration, and ozone filtration.” Then they mixed the water with potassium hydroxide (a form of lye), potassium bicarbonate (sometimes used in baking powders), and magnesium chloride (a salt used in nutritional supplements and for de-icing roads).

Last, the company claimed to the DOJ that it used a “proprietary ‘ionizer‘ apparatus to apply an electrical current to this mixture, which allegedly creates positively-charged and negatively-charged solutions. [The Joneses] then discard the positively-charged solution and store the negatively-charged solution.”

But we may never know the exact step that went wrong, because—according to FDA investigations—almost everything about the company’s manufacturing process was rotten. The DOJ lawsuit notes that Real Water failed to identify manufacturing hazards, implement preventative controls, or monitor for problems. The company also failed to adequately clean and sanitize its equipment and sample and test cleaning solutions—which it recycled and used to clean its 5-gallon water containers. Real Water didn’t label products with production codes that could identify problematic batches or test product samples for quality.

The company didn’t even have any documents of the ingredients and manufacturing process for the water products it made, which could—among other things—help ensure that excess amounts of ingredients weren’t added or environmental contaminants didn’t get in. There was “no written process control and/or supply-chain control procedures to ensure that the correct type and amount of chemicals are added to each batch of product water,” the DOJ said.

While the mystery remains, CDC investigators note that unusual clusters of illness can be an early flag of dangerous products. When the investigators searched hospital billing codes for “toxic liver disease” or “hepatic failure, not elsewhere classified,” they noted an unusual uptick in cases during October and November of 2020. “This investigation illustrates the importance of reporting unusual illnesses to public health authorities,” they concluded.