As America bustled through key political moments last week, with voters casting Super Tuesday ballots and President Joe Biden laying out his national priorities in the State of the Union address, China was busy conducting the largest annual showing of its own political process.

In Beijing, where thousands of delegates from around the country convened for a largely ceremonial meeting to rubber stamp a yearly agenda set by the Communist Party-controlled government, the focus was on domestic concerns – from economic goals to hailing the leadership of Xi Jinping.

But looming over that gathering was also the near certainty that former President Donald Trump would run against Biden in November elections – and that either winner would continue to drive a tough China policy.

Senior Chinese leaders didn’t publicly mention the American election as the Beijing event got underway. But a key strategy promoted there – to transform the country into a high-tech powerhouse – was widely seen as part of an urgent bid to safeguard the country in the face of Biden administration technology curbs and a fractious US-China relationship ahead.

Top diplomat Wang Yi flashed a clearer sign of the anxiety underlying that strategy during a press briefing on the sidelines of the gathering. There, he reached for some of his most dramatic language to date on US trade and tech controls targeting China, saying they had hit “bewildering levels of unfathomable absurdity.”

Behind closed doors, however, observers of elite Chinese politics say, the discussion about the upcoming elections themselves is likely much more direct – especially when it comes to the impact of the return of Trump, who is widely seen as a far more unpredictable force than Biden.

But a return of Trump to office also has the potential to upturn the current geopolitical balance, which has seen America and its allies increasingly united against Russia and the perceived threat of a rising China.

A US retreat from those partners under Trump’s “America First” stance could take pressure off China and present a significant opportunity for Beijing’s own global ambitions.

Officials who are part of the ruling Communist Party’s foreign affairs office have likely been tasked with “scenario-planning and evidence-informed analyses” of the implications of a Trump or Biden win, which would each pose different risks for Beijing, according to Brian Wong, a fellow at the University of Hong Kong’s Centre on Contemporary China and the World.

Experts say Chinese policymakers will be considering how each administration would impact China’s core goal of taking control of the self-ruling democracy of Taiwan, its drive to expand its global power and influence, and its efforts to stabilize and strengthen its already battered economy.

“The priorities are to ensure China remains secure from foreign security and military interference, that it is financially and economically secure,” Wong added.

The Trump effect

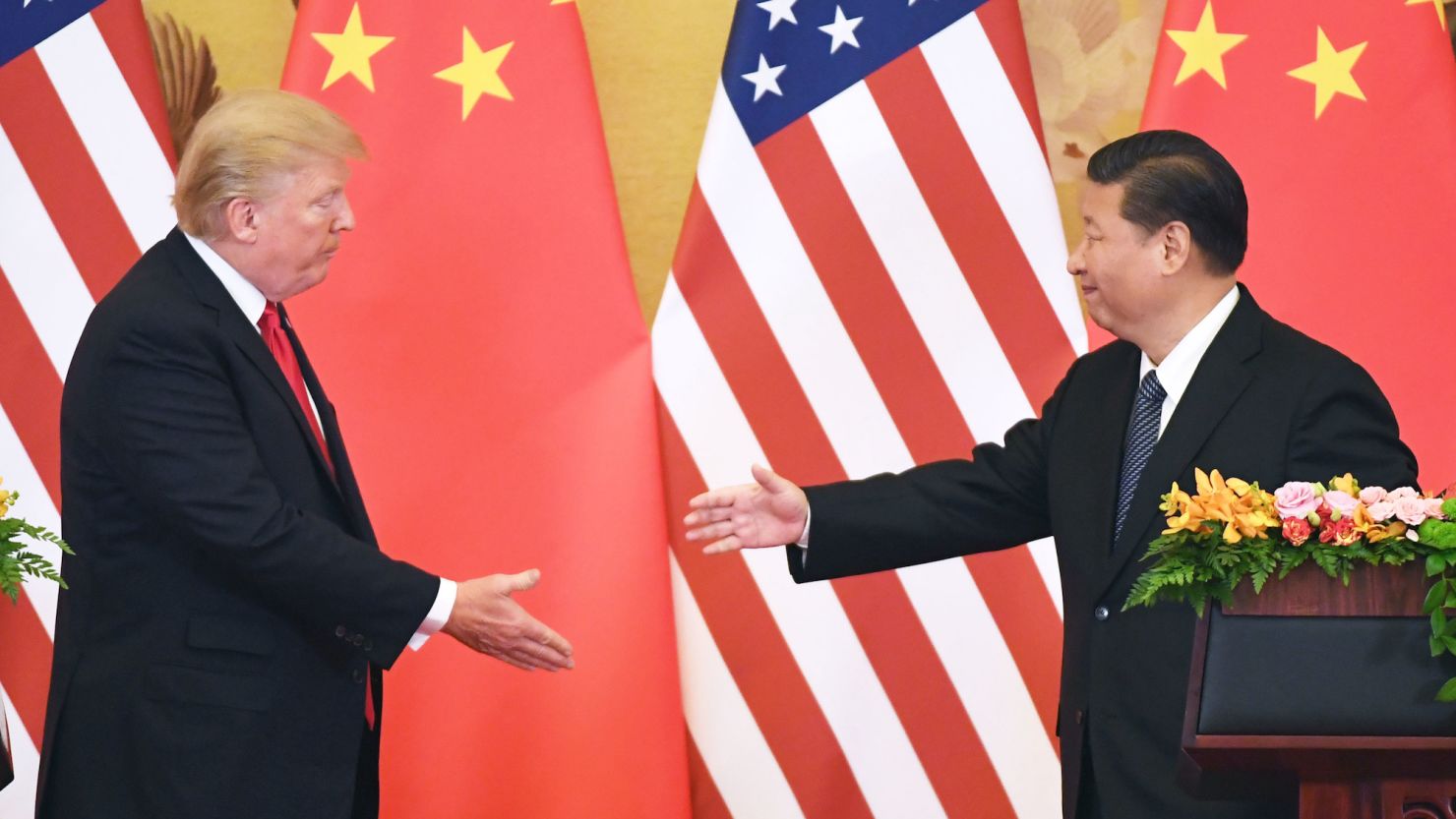

When Trump arrived in the White House in 2017 as a political newcomer, Xi appeared to see a potential opening to strengthen ties that were showing signs of strain during the previous Obama administration.

After being welcomed to Trump’s oceanside Mar-a-Lago property in April that year, the Chinese leader hosted Trump and first lady Melania in Beijing for what was widely described at the time as a “state visit plus.” The president was given rare perks that seemed tailored to appeal to the businessman and former reality television star, including a televised welcome ceremony at the Great Hall of the People and a personal tour by Xi of imperial treasures at the Forbidden City.

Then, Trump lavished praised on his host, saying they had “great chemistry,” and calling the authoritarian leader “a very special man.”

But within a year the relationship had turned contentious as Trump unleashed a major tranche of tariffs – starting with 25% on $50 billion in Chinese goods – sparking an escalating trade war. Relations continued to spiral over a host of issues from US national security alarm over Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei to China’s handling of the outbreak of Covid-19.

This time around, Trump, who is known for his penchant for authoritarian leaders, has continued to praise Xi along the campaign trail. But he’s also drummed up speculation that to combat what he sees as unfair trade practices he could hit Chinese imports with a tariff upward of 60% – and revoke its fundamental “permanent normalized trade relations” status.

A move at that level would create a significant upheaval in trade ties – potentially dropping China’s share in US imports from nearly one-fifth to around 3%, according to analysis by Oxford Economics.

Such controls would come at an extremely bad time for the Chinese economy, which is already facing flagging consumer demand and falling prices amid a host of other issues from high youth unemployment to a property sector scourge.

Economic hardship across China is fueling mounting public frustration – as well as concern about the direction set by the ruling Communist Party leaders, who have long linked their legitimacy to economic stability and growth.

“China must be scared if Trump would return,” said Shanghai-based foreign policy analyst Shen Dingli, pointing to the lack of demand within China to pick up the excess capacity from such a potentially significant drop in exports to the US.

“Without enough to export, enough to be employed, enough to earn money to consume domestically, there would be more social challenges within China,” he said.

It’s unclear if Trump would follow through on such drastic measures, which would be highly controversial in the US and, analysts say, also have a sharp impact on the US economy and jobs, especially as Beijing would likely retaliate. But experts say China’s business and official sectors are likely already considering contingency plans.

More Chinese firms could set up shop in places like Southeast Asia and Latin America to see their goods finished there to dodge the tax. Chinese leaders would likely look to cultivate deeper relationships with other markets – like Europe and their partners across the Belt and Road connectivity initiative – to fill the gap.

A new trade war would also likely see a ramping up of anti-US rhetoric within China – fanned by the government and its online moderators, who would seek to channel any discontent about the economic impact on the US.

Already some chatter can be seen on Chinese social media platforms, where users jeered reports of Trump’s 60% tariff threat, with one writing “the more you add, the better. Americans pay the bill themselves,” and another saying, “if you’re going to decouple, just decouple … we don’t like working 996 (long hours) producing for you anyway.”

China’s bet?

But that doesn’t mean China’s leaders would welcome a Biden win.

The current president is widely seen in China as a more level-headed operator whose interest in global stability makes him willing to work with Beijing in some areas. He’s also a more familiar entity to Xi himself, who has met the president over the course of more than a decade, including when they were both vice presidents.

The two most recently sat down together in November for a summit that achieved the intended goal of stabilizing relations, including repairing a severed high-level military communications line – an outcome widely viewed by the international community as a positive for maintaining peace in a tense Indo-Pacific.

But Biden has sparked fierce disappointment among the foreign policy community in China after coming to office, observers say, as he largely kept the Trump-era tariffs in place – and then added a raft of policy aimed at preventing American high-tech and funding from being used to enhance Chinese military and technological capabilities. Analysts say these controls have, for now, significantly affected China’s semiconductor ecosystem and its development.

The president highlighted those measures in his State of the Union address on Thursday, which came just days after Chinese Premier Li Qiang delivered what is roughly China’s equivalent, the government work report, emphasizing the need for China to boost its own high-tech development and “self-reliance.”

China’s high-tech push stems from several factors, including Xi’s overarching goal of “national rejuvenation” to make China prosperous at home and a dominant power globally. But analysts say the impact of those Biden administration controls – and the prospect of more to come – have raised the urgency of this bid.

Meanwhile, Biden’s careful nurturing of American alliances across Asia – seen in his efforts to bring Seoul and Tokyo closer together on regional security collaboration and military drills, despite their own historical frictions, and his backing of security groupings like AUKUS and the Quad – has made Beijing increasingly wary.

The same is true for the president’s tightening of the US’s transatlantic relations in support of Ukraine against Russia’s invasion – and his success in bringing European partners onside in a bid to “de-risk” supply chains from Chinese goods.

“Biden uses an alliance strategy to isolate China far more effectively than Trump, and while Biden would probably not increase tariffs on China, he could make China’s ability to produce high tech products far less likely,” said Shen in Shanghai, adding “Biden may not be China’s bet.”

Trump sent shock waves through European capitals last month when he said he would not defend NATO allies that failed to spend enough on defense.

The former president has also shown himself willing to launch trade measures against Europe – a move that would be sure to sour relations with a bloc that already views him skeptically for his apparent deference to Russian leader Vladimir Putin, and more recently his efforts to sink a US Congressional deal to fund Ukraine’s defense.

That could open a potentially major opportunity for Xi, whose close ties with Putin and refusal to condemn his invasion have damaged China’s relationship with Europe and set back its longtime bid to drive a wedge between Europe and the United States.

Chinese academics have also noted that “unilateralist” Trump has shown little interest in maintaining an American position leading a global world order – a mantle Xi has been angling to pick up. Trump is also widely seen by Chinese foreign policy thinkers as a destabilizing force for the US domestically.

And in addition to comments about NATO, the former president has also criticized American defense pacts with Japan and South Korea – at several points appearing to threaten to pull US troops stationed in those allied countries.

Diminished American alliances in the region would play to China’s benefit, including when it comes to its designs on the self-ruling democracy of Taiwan, analysts say. China’s Communist Party claims the island as its own, despite never having controlled it, and has vowed to take it, by force if necessary.

Trump has supported Congressional efforts bolstering America’s unofficial relations and defense support for Taiwan. But his talk of a general reluctance to embroil America in costly wars and of diminishing US ties with regional allies has raised concerns among some observers that he could send a signal to Beijing that Washington is not focused on the fate of Taiwan.

The former president’s return to office, however, would make for “less predictability” and could “pose greater tail-end risks when it comes to accidental kinetic escalation induced by posturing from either Beijing or Washington,” according to Wong in Hong Kong.

A second Biden term, he noted, could see a “more successful multi-lateral, concerted effort aimed at containing China,” with a “tacit agreement to not allow for unbridled escalation over Taiwan and the South China Sea,” another pressure point in relations between the two.

Biden has appeared as a staunch backer of Taiwan, at times appearing to step away from America’s policy of strategic ambiguity to say the US would defend the island militarily if attacked (though such statements have quickly been walked back by White House staffers who say the policy remains.)

Together, all this raises a complicated picture for Chinese officials. But it’s also one with a clear bottom line, according to Wang Yiwei, a professor of international relations at Renmin University in Beijing.

“Whoever wins – the structure of (US) confrontation, competition, pressure to China are still there,” he said.

Source: CNN.com