Should You Pack Lunchables for Your Kid’s School Lunch?

CR’s tests found the lunch kits and some similar ones from Armour, Oscar Mayer, and others contained lead and other contaminants, and most were high in sodium

Many kids love Lunchables, the colorful, prepackaged boxes of deli meat, cheese, and crackers introduced in the 1980s. Some parents like them, too, because they’re so easy to pack for school lunches.

They’re so popular that they’re even being served in some school cafeterias, which offer versions with a few tweaks that could imply that they’re a healthy choice for a quick snack or a child’s lunch.

But are Lunchables really good choices for your kid’s lunch? To find out, we tested them and similar lunch and snack kits from Armour LunchMakers, Good & Gather (Target), Greenfield Natural Meat, and Oscar Mayer. We looked for lead and other heavy metals; phthalates, chemicals used to make plastic more flexible and durable, and increasingly linked to health concerns; and sodium, which can raise blood pressure, a concern even among young people. We also compared the nutrition info for the two school lunch versions of Lunchables with their store-bought versions.

The findings: “There’s a lot to be concerned about in these kits,” says Amy Keating, a registered dietitian at Consumer Reports. “They’re highly processed, and regularly eating processed meat, a main ingredient in many of these products, has been linked to increased risk of some cancers.”

We also found that some kits had potentially concerning heavy metal and phthalate levels. And they’re too high in sodium, especially for kids. Do you think the school lunch versions might be better? Sorry: They have even more sodium than the store-bought versions.

Bottom line: “We don’t think anybody should regularly eat these products, and they definitely shouldn’t be considered a healthy school lunch,” says Eric Boring, PhD, a CR chemist who led CR’s testing.

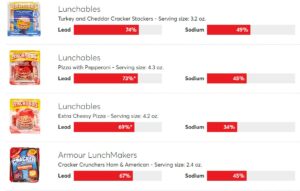

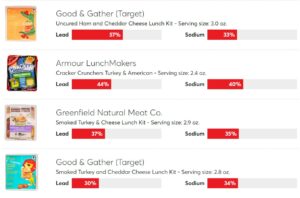

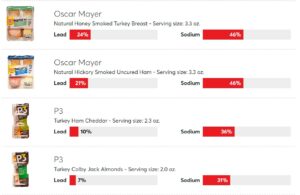

Lead and Sodium in Lunch Products

CR tested 12 store-bought lunch and snack kits for lead and obtained sodium levels from the nutrition labels on each package. Lead is measured in percentage of California’s maximum allowable dose level (MADL). Our experts use this value because there are no federal limits for heavy metals in most foods, and California’s lead standards are the most protective available. Sodium is measured in percentage of the U.S. Dietary Guidelines recommendation.

Contaminants in Lunch Kits

Some contaminants, like lead and cadmium, are naturally found in the environment, which can partly account for their presence in food. But processing can also introduce heavy metals and chemicals found in plastic.

In CR’s tests, our experts found lead, cadmium, or both in all the kits. Even in small amounts, these heavy metals can cause developmental problems in children, as well as hypertension, kidney damage, and other health problems in adults. The risks of heavy metals are cumulative and come from regular exposure over time. The less you consume, the better.

None of the kits we looked at exceeded any legal or regulatory limit. Still, five of the 12 tested products would expose someone to 50 percent or more of California’s maximum allowable dose level (MADL) for lead or cadmium. (Our experts use those values because there are no federal limits for heavy metals in most foods, and California’s lead and cadmium standards are the most protective available.)

“That’s a relatively high dose of heavy metals, given the small serving sizes of the products, which range from just 2 to 4 ounces,” Boring says. For example, the kits provide only about 15 percent of the 1,600 daily calories that a typical 8-year-old requires, but that small amount of food puts them fairly close to the daily maximum limit for lead. Even if one meal kit doesn’t push a child over the limit, it puts them in the danger zone because there will likely be exposure from other sources. So if a child gets more than half of the daily limit for lead from so few calories, there’s little room for potential exposure from other foods, drinking water, or the environment.

We reached out to all the companies whose products had 50 percent or more of the maximum allowable dose level. Kraft Heinz, the parent company for Lunchables, Oscar Mayer, and P3, told CR, “All our foods meet strict safety standards,” and said that “lead and cadmium occur naturally in the environment and may be present in low levels in food products.” Smithfield Foods, which makes Armour LunchMakers, didn’t respond directly to our questions about lead but did say it adheres to “strict programs and policies that promote food safety and quality in every step of our value chain.” Target, which makes Good & Gather products, didn’t respond to our request for comment.

We also detected at least one type of phthalate in every kit we tested except one (Lunchables Extra Cheesy Pizza). According to tests by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, phthalates are present in most people’s blood, which shows just how ubiquitous these chemicals are, something that has raised concerns as more research has linked them to health hazards. Phthalates are known endocrine disruptors, compounds that may mimic or interfere with hormones in the body, which can contribute to an increased risk of reproductive problems, obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and certain cancers. As with heavy metals, the goal should be to keep exposure as low as possible.

The levels in the kits we tested ranged from 0 to 7,412 nanograms per serving. For comparison, in recent CR tests of other packaged foods—including bottled drinks, prepared meals, and fast food—the range was 0 to 53,579 nanograms per serving.

“None of the products exceeded any regulatory limits, but many researchers think those limits are far too permissive, given the emerging research about phthalates harms,” Boring says. For example, DEHP, one of the better-studied phthalates, is linked to reproductive issues, high blood pressure, insulin resistance, and other health problems at levels far below those set by regulators.

Cheese, processed meats, and crackers or pizza—the main foods in these kits—are a trifecta of some of the highest-sodium foods in the American diet.

About 90 percent of U.S. adults and children consume more sodium than dietary guidelines call for. Processed, restaurant, and packaged foods—like lunch kits—contribute over 70 percent of the sodium in the U.S. diet.

Consuming too much sodium can increase blood pressure and lead to hypertension, which is a risk factor for heart disease, stroke, and kidney damage. About 14 percent of children and teens have prehypertension or hypertension, according to a study published in the American Journal of Hypertension in 2021. And kids with high sodium intakes are about 40 percent more likely to develop hypertension than those who have low-sodium diets. “Even if a child doesn’t have high blood pressure now, eating a lot of sodium can mean developing a taste for salt, which can raise the risk in the future,” Keating says.

CR’s tested sodium values, although not exactly the same as the values on the labels, were all within the range permitted by the Food and Drug Administration. But this doesn’t mean that the sodium in these products isn’t a concern.

The sodium counts on the lunch and snack kit labels ranged from 460 to 740 milligrams per kit, which is one serving. Depending on a child’s age, that’s nearly a quarter to half of the daily recommended limit for sodium. “That’s a significant amount of sodium for such a small amount of food,” Keating says. A McDonald’s Happy Meal with six chicken nuggets, fries, and apple slices comes in at 670 mg of sodium by comparison.

Some meal kit manufacturers told us that sodium is an integral part of the foods in their products. Smithfield Foods said, “Sodium is a key ingredient in many of our products and helps us meet customer and consumer demands for quality, authenticity, flavor, and convenience.” The company added, “We provide a broad spectrum of products to meet different needs and tastes, which allows consumers to make choices that suit their individual lifestyles.”

Kraft Heinz and Maple Leaf Foods said they were working on ways to reduce sodium levels. For example, Kraft Heinz said, “We are continuing to reformulate all three brands to reduce sodium, sugar, and saturated fat.” The company also said it has cut the amount of sodium in the crackers included its kits by 26 percent and recently introduced a Lunchables kit that includes fresh fruit.

Maple Leaf Foods, the parent company of Greenfield Natural Meat, which makes a smoked turkey and cheese lunch kit we tested, told us it hopes to offer a reduced-sodium product by the end of 2025.

Another concern is that foods like these are usually packed with lots of additives, such as artificial flavors, carrageenan (used as a stabilizer and texture enhancer), or sodium nitrite. That last one, a preservative in deli meat (as well as in bacon, hot dogs, and other processed meats), can interact with protein to create potential cancer-causing compounds called nitrosamines.

That inclusion of industrial ingredients qualifies these kits as highly processed—or ultraprocessed—foods, says Jennifer Pomeranz, an associate professor of public health policy and management at the NYU School of Global Public Health.

A 2024 review in the medical journal BMJ, which looked at dozens of studies, found a strong link between eating a lot of ultraprocessed foods—sometimes defined as those made with ingredients and methods not typically available in home kitchens and often containing little or no recognizable whole foods—and a higher risk of anxiety, depression, cardiovascular disease, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and colorectal cancer.

Processed meat, a main ingredient in many of these snack kits, poses particular concerns. For example, eating just 1¾ ounces of processed meat a day raised the risk of heart disease by 18 percent in a 2023 analysis that included data from 13 studies involving more than 1 million people. Consuming the same amount of fresh red meat also raised the risk but by just 9 percent.

There also seems to be something about ultraprocessed foods that encourages overeating. “They have all these components—salty crackers and cheese and salty processed meats—designed to hit all of our pleasure centers and make us want to eat more of them,” says Erica Kenney, ScD, an assistant professor of public health nutrition at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

Kraft Heinz took issue with the idea that all highly processed foods are unhealthy. “The classification of foods should be based on scientific evidence that includes an assessment of the nutritional value of the whole product, not restricted to one element such as a single ingredient or the level of processing,” the company said.

But Pomeranz says that the research linking ultraprocessed foods to health risks makes it clear that considering a food’s nutritional content isn’t enough. She notes that some countries have started setting food policies based on how processed a food is. In Belgium, for example, people are advised to limit ultraprocessed foods. In Brazil, ultraprocessed foods that contain industrial ingredients like additives and artificial flavors can’t be sold in schools.

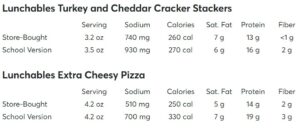

To make meal kits that qualify for the National School Lunch Program, Kraft Heinz created different versions of its Turkey & Cheddar Cracker Stackers and Extra Cheesy Pizza Lunchables. CR didn’t test these two kits for heavy metals or phthalates, but we did review their nutrition information and ingredients lists.

While the school lunch versions of Lunchables aren’t being promoted as health foods, it’s reasonable for consumers to think that they are somehow better than the versions sold in stores. “Having that seal of approval by a school is providing parents and children a message that these kits are a healthy choice,” Pomeranz says.

“From a nutritional standpoint, our NSLP-approved Lunchables can be part of a well-balanced school meal,” Kraft Heinz said.

But experts say that minor changes to these foods can help them squeak by without ensuring they’re significantly healthier. “Food manufacturers are very smart; they can take the guidelines that exist for the National School Lunch Program and tweak products to just meet those guidelines,” Kenney says.

For example, to have Lunchables Turkey & Cheddar Cracker Stackers fit in with school lunch program requirements, Kraft Heinz added some whole grains to the crackers and bumped up the kit’s protein content. The school lunch version of the Extra Cheesy Pizza kit also has more protein.

“Those changes are marginal, and in our opinion do little to improve their nutritional makeup,” Boring says. For example, Kraft Heinz increased the protein in the Turkey & Cheddar Lunchables kit by making the meat portion slightly bigger. That came with “a naturally elevated level of sodium as compared to the retail versions,” the spokesperson said. That natural elevation added 190 mg of sodium to an already high-sodium food, from 740 to 930 mg. The same thing happened with the pizza kit, with 700 mg of sodium in the school lunch version compared with 510 mg in the store version.

A Healthier Lunch Policy?

The U.S. Dietary Guidelines for 2025 are currently under review and could include advice to avoid ultraprocessed foods, Pomeranz says. But federal guidelines don’t prohibit states or school districts from enacting stricter requirements, she says, so they could act sooner.

Ideally, schools would have the funding and facilities to serve freshly prepared whole foods, Kenney says. Right now, that’s often not feasible and would require a revamp of our food system and funding for school lunch programs.

Still, a few changes to the school lunch program could improve the nutritional value of foods served there. Some made in 2010, for example, helped make school meals the most nutritious ones in most American kids’ diets, according to a 2021 study. Recent proposals by the Department of Agriculture to lower limits on added sugar and sodium could help more, even without any restrictions placed on ultraprocessed foods.