I visited a baby elephant orphanage in Kenya — here’s what it was like.

The clapping started immediately.

Behind a roped-off mud pit, over 100 tourists and I watched as a small parade of baby elephants walked single-file from the thick bush, down a dirt road, and up to the handlers awaiting them. They were soon rewarded for their brave entrance with oversized milk bottles and reassuring pats on the head.

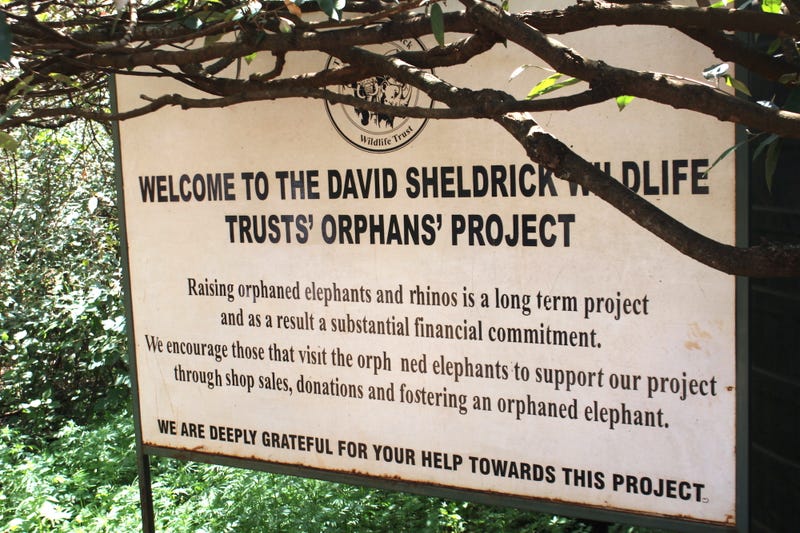

I was at the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust, in Nairobi, Kenya. There was little structure to my visit: Stand behind a rope for two hours as about a dozen 200-lb. toddlers frolicked in the mud, guzzled milk, and carried branches from one spot to another.

In these tumultuous times, I felt lucky to experience such innocence firsthand. Here’s what I saw.

It’s a long, suspense-filled walk from the parking lot to the entrance of the elephant pen. I could sense everyone’s excitement as we struggled to walk in an orderly fashion.

We walked past the emergency vehicles garage, past the gift shop, down through a narrow canopy — until finally the scene unfolded before us.

I was one of the first people to nab a spot behind the rope. The people beside me clutched iPhones, GoPros on extended handles, and long-lens cameras.

Upon first sight of the elephants, a sea of cheers sprang from the crowd. Everyone lifted their phones and cameras in anticipation.

The elephants were released in two waves, since most of them would be hungry and there were only a few handlers to dispense milk bottles. Each bottle held three liters of elephant milk.

Playtime was in full swing. Elephants between 1 month old and over a year gathered in the pen to impress the crowd with their expert branch-handling skills and flopping abilities.

Some made a beeline for the troughs of water, taking gulps and occasionally whipping their tiny trunks at the crowd, casting a fine mist over a lucky few.

But it was quickly on to other, more important matters, such as discovering which mud pit was best.

Rescue teams scour parks all over Kenya to find abandoned elephants. Many are rescued because their mothers were killed by poachers or starved to death. Others became orphans after falling down water holes and being separated from their parents.

Enkesha, the elephant on the left, suffered a nasty trunk wound from a wire snare when she was just a few months old. Poachers use snares to trap elephants in the wild, but Enkesha has made a full recovery.

As friendly as the elephants may be, we were all warned not to crouch down in front of them, since we could have been mistaken for a toy. The elephants frequently play soccer with their handlers.

On this visit, 33 elephants greeted the crowd. Some walked right past us at the rope, letting us pet their backs. Elephant hide is extremely tough, often dirt-covered, and features fine hairs, which elephants have evolved to help regulate body temperatures.

Others find more immediate ways to cool down, such as sloshing around in the mud. Getting out can be a struggle, however, as the elephants are still babies and haven’t quite figured out how their bodies work.

I beamed with pride when this guy finally managed to extricate himself and move onto other fun.

As the day wore on, we were treated to the second wave of elephants. The first group of 15 or so headed off, and the remaining 18 were ushered in. (I had missed this plan early on and was deeply excited to see them coming back.)

Elephants can’t drink any milk except elephant milk, and they’ll typically go through two bottles — or six liters of milk — in a given feeding. I was especially impressed by their ability to hold the bottles with their trunks.

Most of the elephants were well-behaved (moreso than most of the kids I saw that day). Even with so many people furiously taking pictures, the animals kept to themselves.

Except for that one elephant, who all of sudden charged through the rope barrier, which now seemed mostly decorative. Everyone scattered. A woman scooped up her baby and dashed. Nervous laughs were exchanged.

But as the sun rose high over Nairobi, many of the elephants followed up their mud baths with heavy flops onto the dirt. Still jetlagged from my trans-Atlantic flight, I could relate.

Eventually, and most disappointingly, the elephants did have to depart. Everyone rushed to get their last-minute pictures in, scrambling to the furthest corner to be close to them just one last time.

Many of the elephants will stay under the Trust’s care for at least five years, as doctors and keepers nurse them back to health. At that point, they’ll get released back into one of the many parks around Kenya.

After the elephants had ambled home, I couldn’t resist stopping at the gift shop on my way out. Visitors had the option to adopt an elephant or just purchase a commemorative hat, stuffed animal, or carved figurine.

It was hard not to buy up the entire shop, now that I had personally invested my emotions in 33 different baby elephants.

For the briefest and muddiest of moments, all was right with the world.